![]()

Jack Estes is the author of “Searching for Gurney,” one of the books featured in Issue 8 of ODVA’s Veteran News Magazine.

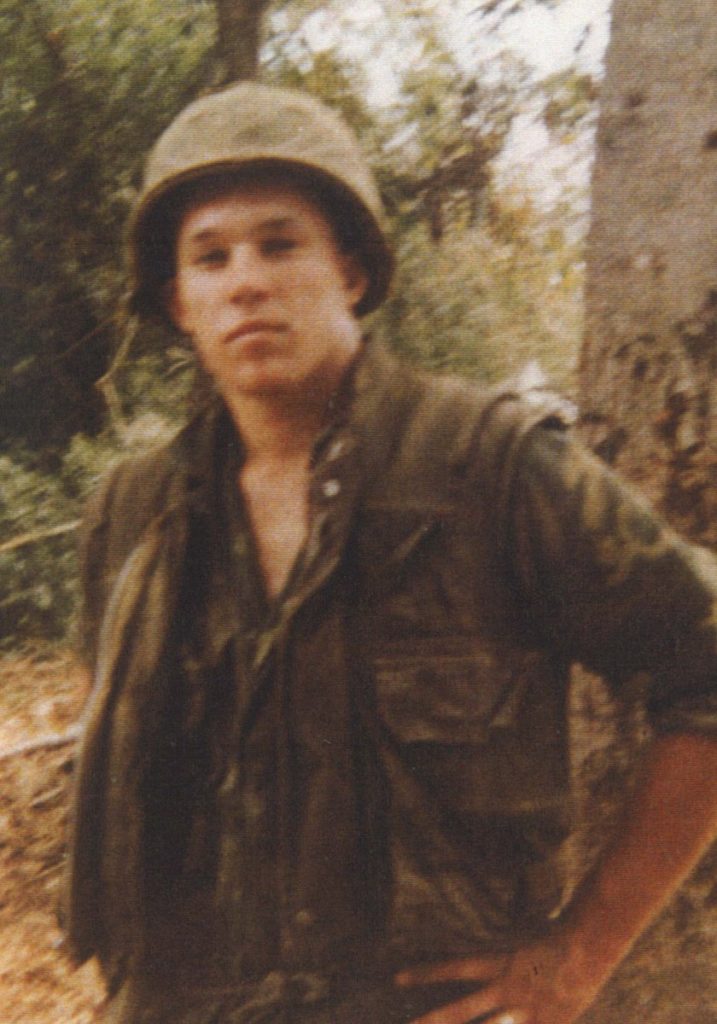

In 1967 Jack Estes had no idea where Vietnam was located or why we were fighting there. He was 18. By the time he was 19 he would know far more about Vietnam than anyone would want to know.

Jack enlisted in the Marines because he thought it would help him grow up. He was flunking out of college, with no money or job, and his girlfriend was pregnant. He needed to pay for the birth of his child.

Estes landed in Da Nang in June to a blast of incredible suffocating heat he had never felt before.

“It seemed to suck my breath away,” he says in his first book, A Field of Innocence.

Jack ended up in the 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines as a rifleman in Vietnam stationed out of Dong Ha, close to the DMZ. His company spent most of their time running patrols in the mountainous jungles. The monsoon rains were hard and constant, as were the firefights.

They found one of the largest enemy caches, with an underground hospital, rockets, artillery, rifles and ammunition. Around the perimeter the NVA had dug in bunkers with bamboo floors and ceilings to absorb the shock waves from B-52’s, which could feel like an earthquake.

It was in this“pockmarked landscape not unlike the green fields of Oregon” that Estes discovered there are brothers and there are friends. They shared not only the experience but they spoke a shared language of war.

After several months of fighting in the jungles and a month in the hospital for two forms of malaria and amoebic dysentery, Estes was no closer to knowing why we were fighting in Vietnam.

He put in for the Combined Action Platoon (CAP) program, a counterinsurgency concept that posted ten Marines, a Navy Corpsman and about a dozen Vietnamese Popular Force solders in the villages. Estes wanted to live in the villages to gain some insight into what the war was really about.

“I had not yet discovered a reason for being there. It wasn’t hell. It was worse. I had to find a reason. on Christmas day I received my order of transfer,” Estes said.

Estes was transferred to a CAP unit in Hue Due, near Da Nang. Instead of the fewer firefights and less humping he expected, his CAP set ambushes and ran night patrols every night. He had lessons in Vietnamese culture and language. His platoon stood guard while crops were harvested, schools built, and they provided medical aid.

He returned to his new wife and baby daughter after a year in this place that was worse than hell. He brought a lot of it back with him mentally and his marriage did not last long.

“Back in 1969 people didn’t like veterans,” said Estes. “It took decades for this to change. For people to realize what they had done and how they were treated as veterans. It was horribly wrong. My friend in the Marine Corps with me shot himself in the head. He lived but he didn’t get disability or treatment for PTSD.

“I had trouble in my mind. This was before I ever heard of PTSD. I tried countless hours of therapy, rap groups and then I started writing about it.”

Estes embarked on a successful real estate career and met his current wife Colleen O’Callaghan in 1982. He credits her with helping him finally deal with his PTSD.

Nearly three decades after returning from Vietnam Estes, his wife and two young children took a trip to Vietnam – to the source of his pain. They carried medical and educational supplies and toys for what was then called Northwest Medical Teams. They returned four times, taking back other veterans and doctors and nurses.

In 1993 Estes and his wife created the Fallen Warriors Foundation to help heal the wounds of war and to honor the sacrifices of American soldiers. They held annual retreats for seventeen years. The retreats were guided by a Zen Buddhist monk named Claude Anshin Thomas. Claude had been a helicopter crew chief in Vietnam and was shot down several times.

“We were doing meditation 20 years ago.” Estes said. “It is now one of the most recognized modalities for treating PTSD.”

Estes was also on a journey to try and find a PF who stayed and fought and helped save his life. His name was Hein and he had a gold front tooth. He was hard to find and when Estes did meet him he had scraped off his gold cap out of fear. Later he pulled the tooth from his pocket. Weeks later he asked if Estes would build a road to his village.

Estes found traveling back was of tremendous help on this mission of healing and traveled back several more times, leading a group of Vietnam Veterans who also carried donations. Soon they were leading groups of doctors and nurses to Vietnam to help provide care to the poorest villages.

“As you get older your strengths changes and …you’re not really actively angry,” said Estes. “A lot of people are better but that doesn’t mean you are ever rid of PTSD.”

In the twenty-five years of its existence, the foundation delivered tons of donations of medical and other critical supplies, built a clean water system for one village that had none, and sponsored many educational programs for Vietnamese children. The foundation also held annual retreats for veterans and their loved ones. The foundation was discontinued just a few years ago.

“PTSD doesn’t mean you’re bad it doesn’t mean you’re weak,” Estes said, “The best thing is to seek out help. You have to try different things to see what works best for you. A good first step is to be with other veterans. You share a commonality. It makes you stop thinking that you’re so much different than other people in the world.”

In 2014 Estes published A Field of Innocence as part of his journey to deal with what we now call PTSD. It is a memoir concerning his time as a young Marine in bootcamp and Vietnam. Estes tried to find a publisher for a couple years until his wife located a small literary press called Breitenbush. It was a finalist for the Oregon Book Awards. Then it sold overseas and was picked up by Warner Books.

A year later he followed up the gripping novel A Soldier’s Son and most recently, the well-received Searching for Gurney.

Estes, who retired as a regional manager for a national commercial real estate firm, attended Portland State and Southern Illinois University. He became a National Collegiate Speech Champion, talking about war and the mental and physical damage it does to soldiers and their families. Estes has continued to be an advocate of healing for Vietnam veterans with articles and essays which have appeared in Newsweek, Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune, LA Times, San Diego Tribune, The Oregonian, and other publications. Links to many of his essays and articles can be found at his website at jackestes.com.

Jack and Colleen have three grown children and reside in Lake Oswego, Oregon.

Views: 1071