![]()

Black men and women have fought and served in every war and conflict in United States history, from the Revolutionary War to the post-9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Ninety African American service members have been awarded the Medal of Honor — the nation’s highest and most prestigious military decoration.

Yet, throughout most of American history, Black service members were segregated, forced to serve in separate units from their White counterparts. Desegregation didn’t occur until Jan. 26, 1948, when President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981 directing the integration of the United States Armed Forces.

Black people, both slave and free, served on both sides during the Revolutionary War and in the War of 1812 (1812-1815). Many served with the British to gain their freedom and resettle in non-slave nations, particularly Canada, Bermuda and Sierra Leone.

Nearly 200,000 Black Americans fought for the Union Army and Navy in the Civil War, accounting for approximately 10% of the Armed Forces. An estimated 40,000 Black soldiers died over the course of the war — 30,000 of infection of disease. A lesser number of African Americans were used as laborers on the Confederate side.

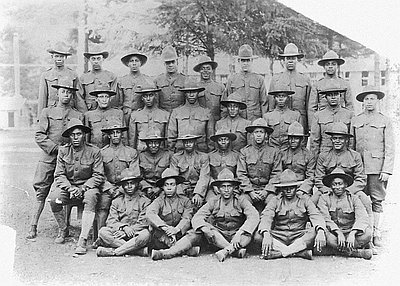

After the war, six regiments of African Americans were established, including one company stationed at the Vancouver Barracks in Washington in 1899 and 1900. Known as the Buffalo Soldiers, they served with distinction in the Indian Wars from 1863 to the early 1900s and in the Spanish-American War in 1898.

The Vancouver regiment participated in military, political, and social activities, introducing many residents of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho to Blacks and raising local awareness of the national policies and practices that beleaguered African Americans.

See ODVA’s blog next week for more information about the Buffalo Soldiers and their legacy in Oregon’s military history.

Between 370,000 and 400,000 African Americans service members served in Europe during World War I, at a time, sadly, when violent racism was rampant in the United States. According to Library of Congress historian Ryan Reft, Black soldiers were often required, especially in the South, to “go out almost dressed as labor gangs, and not in uniform, because the military was afraid of offending white … sensibilities,” he said.

“It’s literally dangerous to wear a uniform in some places,” he said. “And in some places [black soldiers] are attacked and forced to take them off.” It was different overseas, he continued, where “they could wear that uniform, and be proud of being American in service and not worry about being targeted negatively.”

During World War II, an estimated 1.3 million African American soldiers served in all fields of service.

At the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, General Eisenhower was severely short of replacement troops for existing all-White companies. Consequently, he made the decision to allow 2,000 black servicemen volunteers to serve in segregated platoons under the command of white lieutenants to replenish these companies.

These platoons would serve with distinction and, according to an Army survey in the summer of 1945, 84% were ranked “very well” and 16% were ranked “fairly well.” No Black platoon received a ranking of “poor” by White officers or soldiers who fought with them.

However, these platoons were often subject to racist treatment by White military units in occupied Germany and were forced back into their old, non-combat service units before the end of the war. Though temporary, the experiment with Black combat troops proved a success — a small, but important step toward the permanent integration that would soon occur during the Korean War.

One of the most celebrated Black military units was the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of primarily African American fighter and bomber pilots who fought in World War II. They formed the 332d Expeditionary Operations Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the United States Army Air Forces.

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American military aviators in the United States Armed Forces.

See ODVA’s blog the week of February 23 for more information about the Tuskegee Airmen, including several who had ties to Oregon.

About 600,000 Black service members served in the armed forces during the Korean War, and another 300,000 did so in Vietnam. Today, more than 17% of the nation’s 1.3 million service members are black, despite representing only 12% of the U.S. population as a whole.

Black Americans have also held some of the top posts in the country’s include U.S. Army General Colin Powell, who served as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1989 to 1993 and was the country’s first Black secretary of state from 2001 to 2005, and Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, who was sworn in January 2021.

Views: 1583